News Story

A Challenging Road Ahead to Eco-Friendly Refrigerants

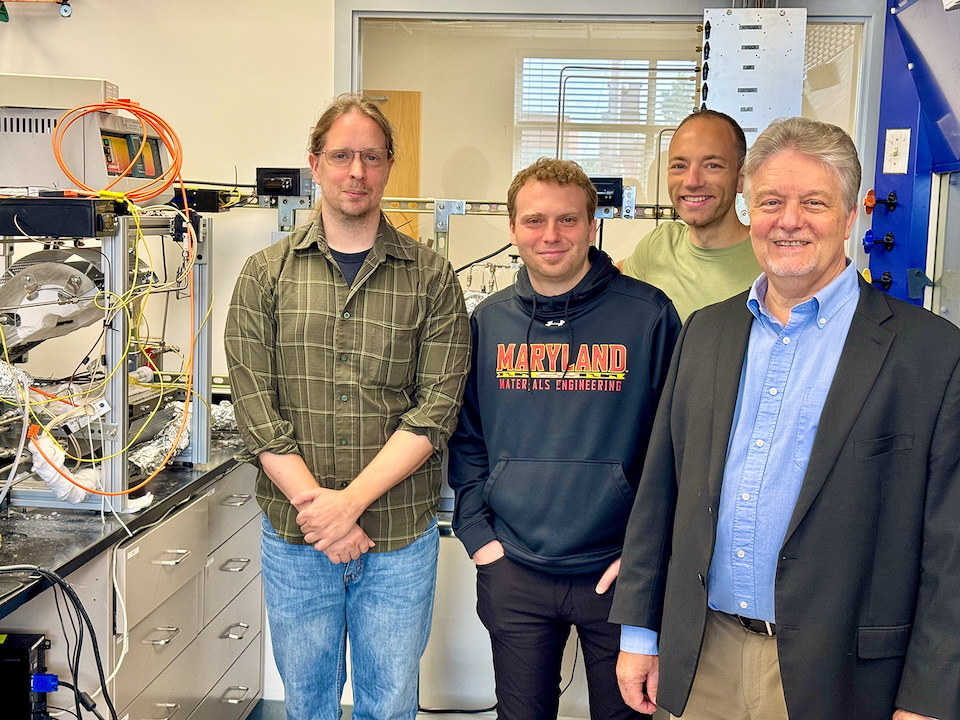

CEEE Director Reinhard Radermacher (standing) leads a breakout discussion session about research needs related to commercial refrigeration refrigerants.

As the federal government continues its push to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and slow climate change, more than 100 stakeholders from government, industry and academe met earlier this month for a workshop co-hosted by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Energy Engineering (CEEE) to discuss the path forward toward adopting more eco-friendly refrigerants, without sacrificing safety or efficiency. The workshop was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

In line with the global objectives outlined in the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act of 2020 mandates a U.S. phasedown of climate-damaging hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants. Federal restrictions on the installation of some heating, ventilation and air conditioning equipment will come into effect as soon as January 2025. While eco-friendly alternatives are available, the transition to the new refrigerants poses multiple challenges — chief of which are safety concerns.

“Many of the proposed refrigerants are either flammable or mildly flammable,” says CEEE director Reinhard Radermacher. “Air conditioners leak from time to time. And when that fluid leaks out, if it's flammable, it could start a fire.”

While HFCs are less damaging than ozone-depleting refrigerants of the past, they still have significant global warming potential (GWP) and are known to contribute to climate change. A switch to ultra-low GWP refrigerants could help slow climate change, but the current possibilities all have drawbacks, making the transition challenging. Ultra-low GWP alternatives include flammable A3 refrigerants, like propane. Other options are mildly flammable A2L refrigerants, including hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) and HFO blends, but some research indicates that many of these refrigerants decompose into per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), known as “forever chemicals” and associated with health concerns. Other ultra-low GWP possibilities include ammonia, which has toxicity concerns, and CO2, which operates under high pressure, making it suitable for only specific applications currently, like supermarket refrigeration.

Entitled “Ultra-Low GWP Refrigerants for Refrigeration, Water Heating and HVAC Applications,” the May 1 and 2 workshop brought together stakeholders to discuss the future of refrigerants. “The purpose of the workshop was to gain an understanding of the challenges of transitioning to new refrigerants and to discuss what type of research DOE should support to address those challenges,” Radermacher said.

“Many of the proposed refrigerants are either flammable or mildly flammable,” says CEEE director Reinhard Radermacher. “Air conditioners leak from time to time. And when that fluid leaks out, if it's flammable, it could start a fire.”

CEEE Director Reinhard Radermacher

The meeting came one month after the DOE released Decarbonizing the U.S. Economy by 2050: A National Blueprint for the Buildings Sector, a comprehensive plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from buildings by 65% by 2035 and 90% by 2050. “There is a sense of urgency in what we want to do,” said keynote speaker Ram Narayanamurthy, deputy director of the DOE’s Building Technologies Office. He noted the importance of a holistic approach to decarbonization that takes into account health concerns, workforce opportunities, life-cycle analysis of the equipment, costs and serviceability. “We understand that buildings are not just inanimate objects. This is where we live. . . . This is where we work.”

Presenters included representatives from manufacturers in the heating, ventilation, air-conditioning and refrigeration industry; safety standards organizations; trade associations, government labs and academe. Representatives from Europe and Asia presented information about their regions’ adoption of ultra-low GWP refrigerants.

Workshop presenter Peter Sunderland, a professor with the University of Maryland Department of Fire Protection Engineering, explained that, by nature, many ultra-low GWP refrigerants are either flammable or mildly flammable. “The chemistry that allows them to break down in the atmosphere also allows them to burn or explode,” he noted. He spoke about the need to mitigate fire risk with improved leak sensors that can quickly and accurately detect leaking flammable refrigerants. “More research is needed to improve sensors and develop standard test methods for sensors,” advised Sunderland, whose UMD lab tests a variety of sensors for industrial partners.

After a full day of presentations on the first day of the workshop, participants divided into smaller groups on the second day to identify concerns where further research is needed. They suggested several areas, including leak prevention; the development of more accurate, longer-life sensors; technology to minimize the amount of needed refrigerant; and methods to improve the efficiency of ultra-low GWP refrigerants to match that of current refrigerants.

DOE plans to use the suggestions to inform their research directions, and will continue to get input from stakeholders on this pressing issue. As a follow-up to the workshop, DOE will convene two working groups, one focused on Codes and Standards and a second on R&D initiatives. CEEE is in close collaboration with DOE on efforts to accelerate the market introduction of ultra-low GWP refrigerants in the HVAC sector. “As one of the key research centers in the nation on environmentally responsible, economically feasible HVAC&R technology,” said Radermacher, “we plan to be involved in whatever working groups come out of that event and to continue to work with the stakeholders to find ways to adopt safe and efficient alternative refrigerants and systems with the least possible contribution to global warming.”

Published May 23, 2024